Please note that there is now a new article on heat acclimation available with up-to-date research. Read it HERE.

When you sign up for a race like the Marathon des Sables (MDS) in the Sahara, or any other event in a similar climate, it becomes important to understand the conditions in which you will compete. Not only is exercising in an extremely hot environment tough, but over heating is a very real risk. It can lead to milder problems such as heat cramp or heat exhaustion, or to the severe and life threatening condition heat stroke, in which the the body’s mechanism to control temperature regulation stops working. If you are adapted to the heat, your body can cope a lot better with the heat stress and you will therefore increase your chances of having a successful and enjoyable race experience.

Whilst I focus this article specifically on MDS, it is highly relevant for anyone who is going from a more “normal” temperature to a hotter environment. For example this can be Marathons in the spring or summer when the weather can shift quickly. If you are unlucky you might be racing during a “heat wave” but not having had the chance to train in these conditions. Monitoring the weather forecast and making some preparations can be time well spent.

Acclimation vs Acclimatisation

Many people taking part in the Marathon des Sables don’t live somewhere where dry 40 degree heat is normal or easily accessible. In this case, heat adaptation prior to the event should form part of your training and preparation. Heat acclimation is used to describe the adaptations that take place in the body in response to heat stress in a controlled environment. Heat acclimatisation on the other hand, generates the same adaptations but occurs in a natural environment. For example, if you would travel to the desert two weeks before the race you would be acclimatising, whereas if you were to stay in for example the UK but follow a heat chamber protocol in the final two weeks you would be acclimating. In this article I will be discussing what happens in the body when you adapt to heat and what you can do to acclimate if you are unable to adapt in the real environment.

How the Body Gets Rid of Heat

The body has four mechanisms to prevent over heating: conduction, convection, radiation, and evaporation of sweat. When the ambient temperature is hot, then the first three mechanisms result in only negligible heat loss if any at all. This leaves us with evaporation of sweat as the only method by which the body can effectively regulate temperature under these conditions, and also the only mechanism that we can impact through acclimation.

When the core temperature rises in the body, we need to cool down. The blood vessels dilate and the heart pumps warm blood out to the skin. There, some heat can be lost through conduction, convection or radiation if the conditions allow, whilst the majority will be lost through the conversion of sweat to vapour. Note that it is not the sweat itself that cools the body down, but the evaporation of it from the skin, a process which requires heat. The more we sweat, the greater the evaporation and the greater the cooling. However, the heart is hard at work which you have probably experienced if you have exercised in the heat. Firstly, it must supply a greater network of arteries with blood than when at normal temperature. In addition, fluid in the blood is being filtered out and lost as sweat. Consequently, the blood volume returning to the heart with each beat decreases. This means that the heart has to work harder to supply the body’s organs with oxygen and keep the blood pressure up.

The good news is that we can get more efficient at managing temperature regulation.

Adaptations to Heat

So, what are the adaptations that take place as you get more used to a hot environment? In summary, the following happens:

- You sweat more, in other words your sweat rate increases. This means that more sweat can evaporate and you can cool down better.

- You start to sweat earlier, e.g. at a lower body temperature than before acclimation.

- You lose less sodium in your sweat and urine, e.g. the salt concentration in the fluids lost decreases. This is the body’s way of maintaining the salt balance in your body.

- Your heart rate decreases. This is a result of your blood volume increasing and an improved blood pressure response. Since the body is now losing more fluid through sweat, the blood volume increases so that blood pressure can be more easily maintained.

- There is a reduction in core temperature compared to the same effort level before acclimation as your body is now more efficient at cooling itself down. Therefore, your overall ability to perform in the heat has increased and your perceived rate of exertion has decreased. You feel more comfortable.

Methods of Heat Acclimation According to Research

So, in what ways can you prepare?

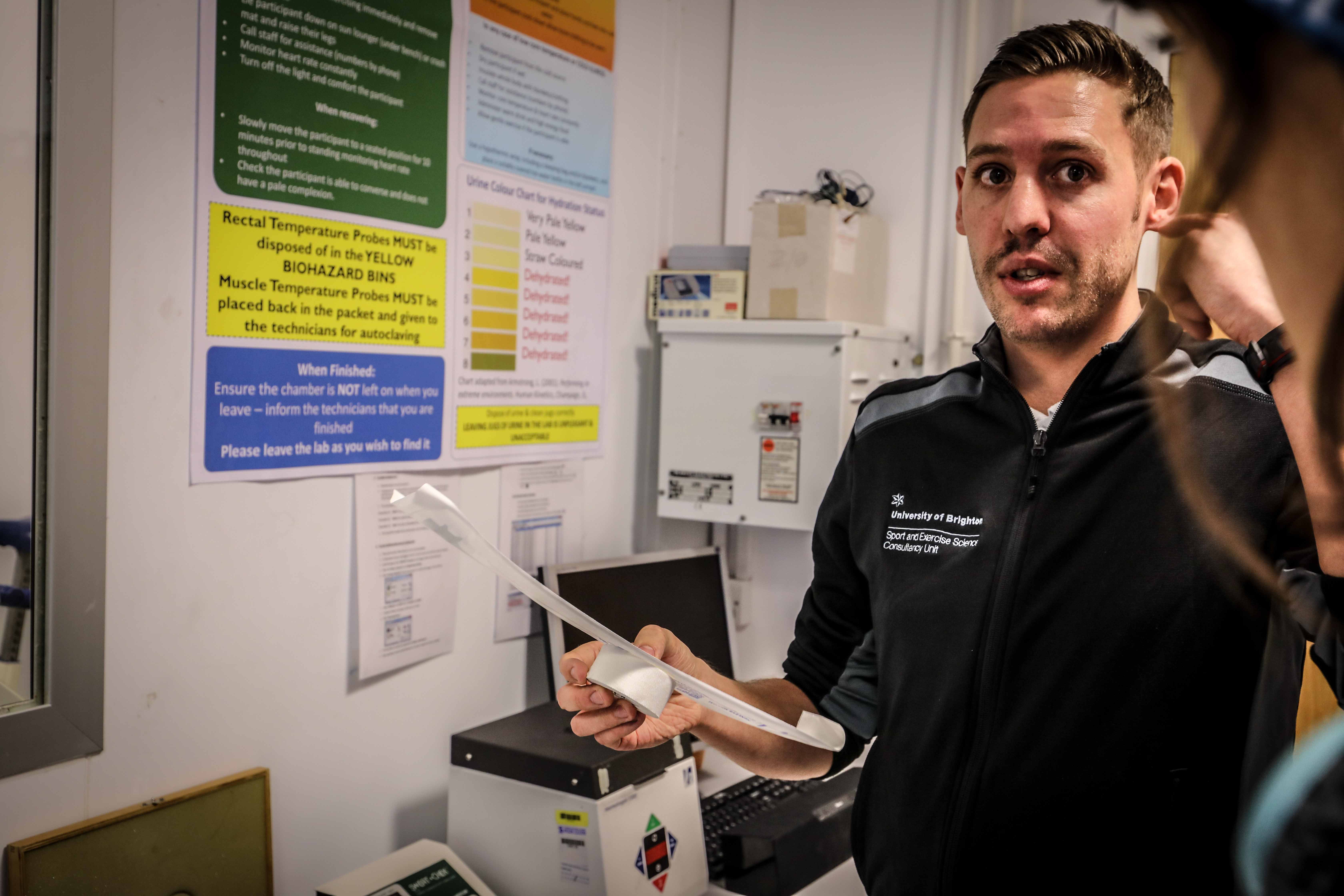

I have been fortunate to be able to work with Dr Ash Willmott and his team at the University of Brighton’s Environmental Extremes Laboratory. Dr Willmott and his team are very knowledgeable, have published numerous research studies on the theme of heat acclimation, and have been supporting both elite and amateur athletes heading for extreme events such as the MDS. I can highly recommend them and their facilities if this is an option for you. Several universities in the UK with sports science facilities have environmental chambers and some open these to the public.

I personally feel that heat chambers offer an advantage over other methods in that they simulate the race experience the closest. You understand what it feels like running in the heat, how your pace will be impacted, what happens to your heart rate, what gear you might get chafing from and so on. It is also a safe, controlled environment with professional support.

However, access to environmental chambers can be difficult and costly so what else can you do? And if you do use one, what is the best protocol for when, how often, how long for etc?

Plenty of research has been conducted to show that acclimation using various methods and protocols can be effective in inducing heat acclimation. In order to translate this into practical implications for you as a runner preparing for your race, and get the current latest and greatest thinking on heat acclimation, I caught up with Dr Willmott to get a few questions answered:

If heat acclimation is conducted using a heat chamber, what is your view of the optimal protocol?

To optimise heat adaptations, it is recommended to do heat acclimation every day for a minimum of four to five days but up to 10-14 days before departure to MDS. For example Monday-Friday for two weeks with the weekend off. These sessions would last a minimum of 60 minutes, possibly up to 90 minutes, in the heat chamber. It is thought that the longer you remain hotter with a core temperature at around 38°C– 38.5 °C the better. Of course, every day may not be practical for a lot of people but an hour every day will still be beneficial, or, as I concluded in my PhD, doing twice daily sessions every two to three days would be another option.

Are there any shorter or alternative protocols that could work for those really restricted on time?

Yes, there are. We did actually conduct a study on a short term acclimation process, performed over only 4 days. This showed great result primarily on the perceived adaptations (comfort in the heat, thermal sensation and perceived exertion), but the sweat rate increased by 14% and plasma volume also increased so there were physiological benefits too. I have also conducted research showing that twice daily sessions over two days with 8 hour recovery could still be beneficial.

Not everyone can get to a heat chamber. For people with logistical or budget constraints, what tips do you have?

We are now actually looking into alternate methods of heat acclimation without having to use a heat chamber. For example there are proven benefits to sauna exposure, hot bathing or exercising using a sauna suit. One study on baths shows heat adaptation after spending just 10-20 minutes in 40°C after exercise and gradually building this to 30-40 minutes. A sauna study shows heat adaptation after 30-minute sessions in a Sauna at 87°C immediately following exercise. And, although not published yet, we have ourselves shown that running or training whilst wearing a sauna suit can help induce adaptations and still enables the quality of training in terms of intensity. The sauna suits are cheap, accessible and enables you to do the training anywhere.

Typically, we still see larger magnitudes in heat adaptations whilst exercising in the heat chamber or in the conditions of the event (hot dry or hot humid) compared to these three methods or just sitting in the heat. This is due to the increased and prolonged physiological strain which increases the core and skin temperature, induces profuse sweating and lasts longer than 60 minutes over 5-10 days.

For us it is also about the education runners receive whilst running in the heat chamber, learning about their own sweat rate, sodium levels, heart rate zones, predicted race pace, thermal sensation and comfort. We can inform runners on how hot they are when they feel hot, and this helps them to recognize cues as to when to stop and take on fluids, slow their pace etc. Even just one session can help inform if the runner is of a high or low acclimation state which informs us if they are at risk of heat related illnesses.

Some people have asked me if they should avoid drinking during heat acclimation sessions. What are your thoughts on this?

There is some now dated evidence that not drinking could accelerate heat adaptations but this has since been dismissed. One reason why some practitioners may suggest no drinking is to accurately work out sweat rate, however this should really only be done on the first and last heat acclimation session to evaluate the efficacy of heat acclimation. If you are dehydrated or dehydrate quickly you could be at risk of heat related illness. I would definitely recommend starting any heat acclimation session hydrated and whilst it is important to not drink too much, you should take on fluid to thirst. Hydration status can easily be measured by checking colour of urine against a typical scale and/or by conducting a daily early morning weighing to monitor body mass changes over the course of heat acclimation.

Further Thoughts from the Athlete & Coach Perspective

So, now you have a pretty comprehensive insight into how you could go about acclimating to the heat. We have seen that running on a treadmill in an environmental chamber, every day or so for 10-14 days prior to the race is preferred for optimising adaptation but that you certainly can choose a more accessible method or do a shorter or less frequent protocol of heat chamber running.

Hot Yoga and Other Methods

Based on my own experience, and following the logic resulting from the research studies, if you can find a way of doing exercise in a hot environment, that raises your core temperature to sufficient levels for a long enough time, you can induce adaptations. For example, whilst I am a great fan of the heat chamber method, I like doing hot yoga and I have had great success with it. Hot yoga can vary in intensity, heat of the room and class duration however. To maximise heat acclimation, it would seem that perhaps a 75-90 minute high intensity class that gets your heart working would have the most effect. However, you may need to start easier and build to that. Choose classes based on what suits you as an individual. I don’t recommend leaving these sessions to last minute if you have not done hot yoga before. You may discover all sorts of new muscles with resulting aches and pains. This may impact your race preparations negatively.

Some people construct their own heat chambers at home. Whilst this certainly is possible I would just issue a word of caution. Heat related illness can be very serious and come on quickly. Never exercise alone in the heat. A supported environment is much safer.

Of course you are not restricted to a single method. Why not mix and match!

A note on tapering

Heat adaptation should take place in the final two to three weeks before the race. This coincides with your tapering. It also, for many, coincides with the last minute pre-race panic, stress and maybe some sleepless nights. Don’t put undue pressure on yourself during these weeks. If you have a daily or near daily heat acclimation session in the form of heat chamber, yoga, or running with a sweat suit, don’t add more training on top. You need to arrive at the start line fresh and rested and every day in the final couple of weeks should gradually take you there. Don’t overdo it!

Further Reading, Resources & References

Here is a related article on heat acclimation that goes into a bit more detail on what might happen when you step into an environmental chamber.

Read more about the Environmental Extremes Laboratory

Twitter: Follow Dr Ash Willmott and the Environmental Extremes Lab

If you are interested in bespoke coaching for MDS, check my coaching services here.

References

https://www.humanistforlag.no/paa-livets-grense-hvordan-kroppen-takler-ekstrem-natur.5964465-325676.html

(2016) Short-term heat acclimation prior to a multi-day desert ultra-marathon improves physiological and psychological responses without compromising immune status, Journal of Sports Sciences, 35:22, 2249-2256

Disclaimer: Should you wish to put into practise any information provided in this blog you do so at your own risk.

Hi,

Thank you for your advices! I’m from Finland and I’ll be running on MDS in few weeks. I’ve also done some training in heat chamber. You were talking about core temerature, but what is the temperature in your heat chamber while running?

BR

Arttu

Hi Arttu, you get adaptations from about 35 degrees. If I do heat chamber for MDS I would go up to towards 40 degrees if it is dry heat, which ideally you should have for MDS prep as the heat is dry in Sahara and not humid. Good luck!

Very comprehensive and insightful. Thanks for taking the time to put this post together.

Thank you!