This is the second article in a series of three on preparation strategies for the Marathon de Sables. In the first article we discussed various aspects of heat acclimation. This article is a continuation, and we will talk about heat acclimation for women. As with the previous article, I thank Drs Ash Willmott, Jessica Mee, Justin Roberts and Neil Maxwell for their contributions and for taking the time to respond to my questions.

How does heat acclimation differ for women, if at all?

With regards to female-focused heat acclimation, there is still limited research available . Evidence so far suggests that the magnitude of adaptations towards repeatedly exercising in heat stress are similar between male and females. However, females require additional days/sessions of heat acclimation to achieve the same magnitude of physiological adaptations as males.

So, women need more heat acclimation to achieve the same adaptations as men?

Yes, for example, in one study females required 10-20 days to obtain comparable reductions in resting core temperature (-0.2 to -0.4°C) and heart rate (-10 to -24 beats per minute), as opposed to males who only needed 5-10 days (Wyndham et al., 1965; Mee et al., 2015).

When focussing on just female-related research, a longer protocol (5-9 days) was required to observe specific reductions in exercising core temperature (-0.2°C) and heart rate (-5 beats per minute), compared to the first 4 days of heat acclimation (Kirby et al., 2019).

Women need 6-10 days to improve their performance

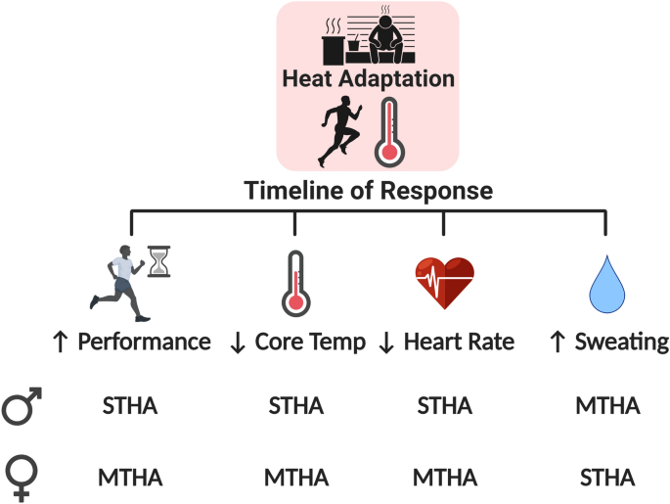

The figure below (Wickham et al., 2021) displays the temporal sex differences for heat acclimation measures, where it demonstrates females need medium-term heat acclimation (MTHA: 6-10 days) to improve their performance, core temperature and heart rate. It also shows that fortunately females may see improvements in their sweat rate following short-term heat acclimation (STHA: ~5 days). However, the higher sweat rate may have implications on hydration strategies (as greater fluid loss = greater replenishment).

Therefore, when preparing for endurance events in heat stress, females may wish to start heat acclimation earlier, engage in repeated blocks of heat acclimation and/or complete additional heat stress exposures compared to males.

What are the reasons for these sex differences?

These sex differences likely arise because females experience less physiological stimulus during heat acclimation compared to men. For example, the magnitude of increased core temperature, amount of heat gain, and resultant heat storage. This can increase the rate at which physiological and performance adaptations to heat acclimation are obtained (Wickham et al., 2021).

Female physiology and performance in the heat

On average, females typically have a smaller body mass, higher fat mass, and a smaller body surface area than males. They do however have a larger surface area-to-mass ratio compared with men and this may be advantageous for female long-distance runners to help heat dissipation.

Women have more sweat glands, a higher density of these sweat glands, and use a higher percentage of their sweat glands than men. Despite of this, females demonstrate a lower sweat rate and sweat gland output compared to males when exercising in the heat (Gagnon and Kenny, 2012).

Fluid intake

These sex differences in sweating are relevant to hydration planning for women. Their smaller mass, lower heat generation, and less sweat loss will determine the required amount of fluid intake to maintain hydration status, which will likely be lower than for men. Therefore, fluid-replacement strategies need to be tailored to you individually and certain heat acclimation methods may be more beneficial (e.g. sauna exposure) to facilitate greater sweat adaptations.

Fitness level matters

Increased aerobic capacity (e.g. fitness levels) in females demonstrate partial adaptations to that of heat acclimation. This includes increased plasma volume, decreased cardiovascular strain, and an earlier onset and improved sudomotor function (Fortney and Senay 1979). In addition, improvements to physiological and performance adaptations following short term heat acclimation are more likely to be observed in well-trained female athletes (Sunderland et al. 2008) as opposed to a recreationally active females (Mee et al. 2015; Kirby et al. 2019).

Therefore, women who are preparing for ultra-endurance events in heat stress may wish to focus on improving their overall fitness levels first. This of course should happen in the process of undertaking normal training. Once you have improved your fitness levels you should then undertake medium-term heat acclimation (6-10 days).

How does the menstrual cycle or oral contraceptive affect females in the heat?

In females, thermoregulatory responses vary over the menstrual cycle and at menopause, due to hormone influences (e.g. estradiol and progesterone). During the luteal phase (after ovulation and before menstruation), or in the high-hormone phase of oral contraceptive use, baseline core temperature and the resultant threshold for thermoregulatory control of sweating and vasodilation are increased by around +0.3-0.5°C (Yanovich et al., 2020).

During menopause, females may experience hot flushes too, where there are large changes in the distribution of the blood to the periphery, which can actually result in a reduction in core temperature (Kronenberg, 2010).

Learning your individual response to heat stress is key

The increases in baseline core temperature can result in a higher exercising core temperature, which may compromise performance during prolonged events. However, evidence suggests it is doubtful that the effects of menstrual cycle phase or oral contraceptive use pose significant threat for female athletes (Notley et al., 2021). It is likely that this is due to minimal effects on thermoregulatory function and thermo-sensitivity for whole-body heat loss during self-paced exercise in the heat (Lei et al. 2017, 2019; Notley et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the key is to learn how you individually respond to heat stress whilst exercising and understand how to pace accordingly.

As such, when undertaking heat acclimation bear the following in mind:

1) the acquired thermal load during each session (or over the entire protocol) must be tailored to the individual athlete;

2) apply caution when evaluating the resultant adaptations, as these may be influenced by menstrual cycle phase.

Specific considerations for heat acclimation for women:

- One on hand, if baseline core temperature is increased you may reach a target core temperature of ~38.5°C faster. This could potentially be good for training volume reasons, and may result in a large magnitude of adaptations. On the other hand, we don’t know yet if that may affect the adaptation effectiveness due to less work being required to reach that core temperature and less of a change in temperature from baseline to target. It could potentially result in inferior physiological and performance adaptations. More research is required to understand the effects of an elevated core temperature on effectiveness of the adaptation, but the point is that women should be aware that their core temperature changes with hormonal fluctuations.

- When monitoring and evaluating for core temperature adaptations between pre and post heat acclimation sessions, menstrual cycle should be acknowledged in case sessions fall within different phases. For example, if a female started with a baseline core temperature of 37.7°C, this may decrease to 37.3°C due to the different menstrual phase as opposed to a true adaptation – thus, a false positive.

- It’s important to understand that while males and females experience similar increases in core temperature when exercising at the same intensity in heat stress, females are more likely to report they feel hotter, more uncomfortable, and more unpleasant, compared to males (Schoech et al., 2021).

- For multi-day events it is relevant to be aware of the effects of potential sleep deprivation. Although ~24-hours sleep deprivation does not impair thermoregulatory function, it does exacerbate perceptual symptoms associated with heat-related illness (Relf et al., 2018).

Knowing this information may help females understand their own physiology better whilst preparing for events such as the Marathon des Sables. We advise females to familiarise themselves with exercising at performance intensities under anticipated heat stress across the whole menstrual cycle (Gibson et al., 2020).

Summary: how can women approach heat acclimation?

Women can tailor their heat acclimation to mitigate against the aforementioned sex differences by;

- including additional heat acclimation sessions (medium-term heat acclimation of 6-10 days);

- including a more humid environment (>60% relative humidity or sauna exposure);

- utilising a priming strategy, such as overdressing (e.g. vinyl sauna suits) or passive heat exposure (~50°C) prior to training.

Women may also benefit from a multi-mixed/alternate method including sauna exposure, hot water immersion (i.e. bathing), and prolonged periods of passive heat exposure before/during/after training. This is prescribed across the menstrual cycle to improve heat acclimation efficiency.

As continually stated, caution and health &safety are always advised, and professional advise should be sought before any heat acclimation.

Further Reading, Contact Information, Resources & References

Here is a related article on heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance:

- Gibson, O. R., James, C. A., Mee, J. A., Willmott, A. G., Turner, G., Hayes, M., & Maxwell, N. S. (2020). Heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance: a review and practitioner guidelines. Temperature, 7(1), 3-36.

Twitter:

Dr Ash Willmott – @AshWillmott / https://aru.ac.uk/people/ash-willmott

Dr Jessica Mee – @JessicaAnneMee / https://www.worcester.ac.uk/about/profiles/dr-jessica-mee

Dr Justin Roberts – @drjustinroberts / https://aru.ac.uk/people/justin-roberts

Dr Neil Maxwell – @UoB_EEL / https://research.brighton.ac.uk/en/persons/neil-maxwell

Read more about the Environmental Extremes Laboratory (EEL) = https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/extremeslab/2021/12/13/eel-team-mitigate-effects-of-severe-heat-stress-in-35th-marathon-des-sables-reflections-from-the-athletes-and-team/

If you are interested in:

- Heat acclimation, screening or research aligned to this area – contact Dr Ash Willmott or Dr Neil Maxwell

- Nutrition guidance for endurance and ultra-endurance events – contact Dr Justin Roberts

- Altitude exposure, information and education – contact Dr Ash Willmott or visit Para-monte.org

References:

- Fortney, S. M., & Senay Jr, L. C. (1979). Effect of training and heat acclimation on exercise responses of sedentary females. Journal of Applied Physiology, 47(5), 978-984.

- Gagnon, D., & Kenny, G. P. (2012). Does sex have an independent effect on thermoeffector responses during exercise in the heat?. The Journal of Physiology, 590(23), 5963-5973.

- Kirby, N. V., Lucas, S. J., & Lucas, R. A. (2019). Nine-, but not four-days heat acclimation improves self-paced endurance performance in females. Frontiers in physiology, 10, 539.

- Lei, T. H., Stannard, S. R., Perry, B. G., Schlader, Z. J., Cotter, J. D., & Mündel, T. (2017). Influence of menstrual phase and arid vs. humid heat stress on autonomic and behavioural thermoregulation during exercise in trained but unacclimated women. The Journal of physiology, 595(9), 2823-2837.

- Kronenberg (2010). Menopausal Hot Flashes: A Review of Physiology and Biosociocultural Perspective on Methods of Assessment. The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 140, Issue 7, July 2010, Pages 1380S–1385S.

- Mee, J. A., Gibson, O. R., Doust, J., & Maxwell, N. S. (2015). A comparison of males and females’ temporal patterning to short‐and long‐term heat acclimation. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 25, 250-258.

- Notley, S. R., Racinais, S., & Kenny, G. P. (2021). Do sex differences in thermoregulation pose a concern for female athletes preparing for the Tokyo Olympics?. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(6), 298-299.

- Relf, R., Willmott, A., Mee, J., Gibson, O., Saunders, A., Hayes, M., & Maxwell, N. (2018). Females exposed to 24 h of sleep deprivation do not experience greater physiological strain, but do perceive heat illness symptoms more severely, during exercise-heat stress. Journal of sports sciences, 36(3), 348-355.

- Sunderland, C., Morris, J. G., & Nevill, M. E. (2008). A heat acclimation protocol for team sports. British journal of sports medicine, 42(5), 327-333.

- Schoech, L., Allie, K., Salvador, P., Martinez, M., & Rivas, E. (2021). Sex Differences in Thermal Comfort, Perception, Feeling, Stress and Focus During Exercise Hyperthermia. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 128(3), 969-987.

- Wickham, K. A., Wallace, P. J., & Cheung, S. S. (2021). Sex differences in the physiological adaptations to heat acclimation: A state-of-the-art review. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 121(2), 353-367.

- Yanovich, R., Ketko, I., & Charkoudian, N. (2020). Sex differences in human thermoregulation: relevance for 2020 and beyond. Physiology, 35(3), 177-184.

Elisabet’s comment: There are several apps available for tracking your menstrual cycle. Their main purpose vary, including being a hormone free contraceptive method, planning for pregnancy, and/or tracking for athletic performance. It’s meaningful to track if you are on a nature cycle (or use IUD as it doesn’t down regulate your natural hormones). Understanding the changes that your body goes through over the course of your menstrual cycle is useful when it comes to planning training, nutrition and as we have seen, for better understanding and improving your performance in the heat.