This article on hydration for Marathon des Sables is the 2nd article in our new 2025 series of updated articles related to the preparation strategies for the Marathon de Sables Legendary (MdS) and other ultra-endurance events in 2025. This article is developed with the multi-stage format of the Marathon des Sables in mind, but much of the content is applicable to other race formats where you are facing a hot climate on race day.

For people familiar with the Marathon des Sables prior to the 2024 edition, I want to just highlight one of changes that were implemented at this edition, and that is the removal of the previously compulsory salt tablets that were handed out at the race. As such, having your own hydration strategy for sodium/electrolyte intake during the stages now becomes more important. It is compulsory to bring two stock cubes per day. While these could be an important contributor to your overall sodium intake during the race, and perhaps enough for some, they are not an equivalent replacement of the salt tablets. As an example one Knorr chicken stock cube contains 4,14 grams of salt, of which 1,66 grams is sodium. Not only is this likely to be insufficient as your sole source of sodium (in addition to food), but ingesting a stock cube brings practical challenges, such as how to dissolve it in cold water in the morning if you don’t take a stove. Furthermore, it may not be palatable for all people, and you are unlikely to be able to ingest it during the stage itself. The long stage for example takes 8+ hours, up to 35 hours, to complete. Going into this relying on one or two stock in the morning seems unwise. I suggest that if you are doing the Marathon des Sables and plan to ingest the stock cubes as part of your hydration strategy, that you simply take that into account when reading this article and consider them part of your strategy as a whole.

With that said, I hope you find the following guidelines to help you develop an effective hydration strategy for the Marathon des Sables useful.

As with the previous article, I thank Drs Ash Willmott and Freya Bayne, as well as Professor Justin Roberts and PhD student James Barber for their fantastic contributions, and for taking the time to respond and put this article together.

How to Develop an Effective Hydration Strategy for the Marathon des Sables The Legendary?

For the MdS legendary, competitors will be required to compete in hot ambient temperatures (~40°C) and low relative humidities (~20%). Exercise in hot and dry conditions induces elevations in body temperature (core and skin) which elicits heat loss mechanisms such as increases in skin blood flow and sweat secretion. Sweat evaporation is the primary heat loss mechanism in hot and dry conditions as the sweat will evaporate from the skin surface into the surrounding environment, carrying with it bodily heat. Typical sweat rates in hot and dry conditions are ~1.5-3.0 L per hour depending on heat acclimation status, body size, and, exercise intensity and duration. If you are not replacing what is being lost through sweat as well as in the breath, then you are at risk of becoming dehydrated (>2% loss of overall body water). Dehydration increases physiological strain, which can be measured by increased core temperature, heart rate and perceived exertion. Dehydration puts you at risk of suffering from 1) heat related illnesses (e.g. heat cramps, heat exhaustion and heat stroke), 2) impairments in aerobic performance and 3) impairments in cognitive/mental performance. In addition to the volume of water you are losing, you must also consider the quantity of sodium that you are losing within that volume of sweat. Sodium is a mineral that helps balance water, and control blood pressure and nerve impulses. If sodium is lost and not replaced, you are at risk of suffering from a range of negative conditions including: headaches, dizziness, fatigue, loss of appetite, profuse or sudden sweating, cramps, irritability/restlessness, and seizures and/or loss of consciousness. Therefore, it is important to factor in both water and sodium quantity into your hydration strategy. Based on scientific literature, a “pre-planned hydration strategy” is more effective to avoid becoming dehydrated during multi-stage events compared to a simply “drinking to thirst”. This pre-planned hydration strategy should be trialled prior to competing in the MdS legendary.

1. Understand Your Hydration Needs

Sweat Rate

Calculate your MdS sweat rate by weighing yourself before and after your heat training sessions (factoring in how much fluid has been consumed during or lost through toilet breaks) in similar environmental conditions to the desert. This will help you estimate how much fluid you lose per hour and therefore inform how much you need to be replacing. This can be completed via one heat session in an environmental chamber, pre and post heat acclimation to assess improvements, and/or during a heat training camp session that is conducted in similar environmental conditions to the MdS legendary and other ultra-races.

Here is a brief step by step guide on how to figure out your sweat rate with an example equation below (Figure 1):

1. Empty your bladder and record your body mass (ideally nude body mass)

2. Perform your training session and record exactly how much you drank. This is easy if you drink from a bottle with a known mass. You can easily weigh your bottle before and after and record the difference (1 gram = 1 mL).

3. After exercise, towel dry your whole body and then record your body mass again (preferably nude as sweat loss can weigh down clothes).

5. Now subtract your post-exercise body mass from your pre-exercise body mass to get the amount of sweat lost during exercise.

6. Also subtract the mass of the bottle or bottles before and after to obtain the volume you consumed.

7. You can now calculate your sweat rate by adding your body mass loss and fluid consumed together, minus any fluid loss, and then dividing it all by the time spent exercising.

Figure 1. Sweat rate calculations for an athlete who weighs 70 kg and is exercising for 1 hour.

Sodium Loss

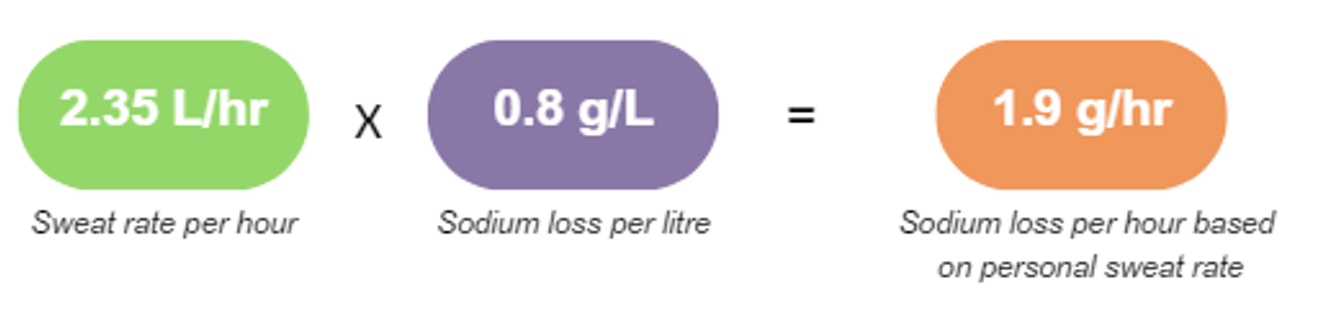

Calculate your sodium loss per litre of sweat. This will help you estimate how much sodium you lose per litre (Figure 2) and therefore inform how much you need to replace per hour (based on your individual sweat rate above; Figure 3). This can be completed at most institutions offering heat acclimation training services or via a sweat test (e.g. Precision Hydration). You may also be able to estimate sodium loss based on visible losses of salt, for example if you notice your clothing is salt stained or you have an accumulation of salt on your temples, you are likely to fall into the higher bands of sodium loss outlined below.

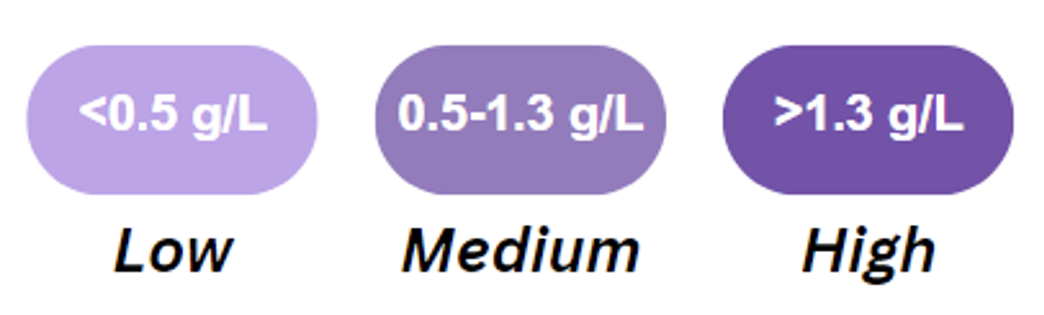

Figure 2. Sodium losses range from low (<0.5 g/L), medium (0.5-1.3 g/L) to high (>1.3 g/L).

Figure 3. Sodium loss calculations based on personal sweat rate of athlete who weighs 70 kg and exercises for 1 hour.

Environmental Factors and Behaviour

As a result of the higher ambient temperatures and dry air, your sweat rate and subsequent sodium loss will be greater in the desert compared to normal UK conditions and as such, the risk of dehydration is greater. Therefore, it is important to 1) educate yourself on the possible risks of dehydration and heat related illnesses symptoms so you can spot them and respond to them faster, 2) practice your pre-planned hydration strategy whilst running in hot conditions (via an environmental chamber or at a training camp that are in similar conditions to MdS legendary), so that you can get comfortable with drinking warm water whilst running as you will not have access to cold water during the MdS legendary, and 3) factor in your pre-planned hydration strategy into your kit check. This includes determining how you will carry your water (e.g. water bottles and/or bladders), the accessibility of your water (e.g. to be able to easily refill at check points, how you will replace/carry your sodium (e.g. tablets and/or powders/effervescent tabs – take min-zip lock bags perhaps), and the accessibility of your sodium replacement (e.g. positioned in outer parts of backpacks for easy access and easily replaced at check points – usually provided by race organisers).

2. Pre-Heat Acclimation and MdS Hydration

Start Well-Hydrated

Attempt to begin your heat acclimation training, the race and/or race stage well-hydrated. This should include water and electrolyte solutions (i.e. tablets and/or sachets). It’s recommended you drink ~5 mL per kg of body mass (e.g. 350 mL for someone who is 70 kg) and consume ~590 mg of sodium ~1-2 hours prior to each heat acclimation session to start your training adequately hydrated. Many sports drinks contain around half this sodium per serving (or less), so if using a particular brand based on preference, we advise you to be mindful of this, as you might want to consume additional salt tablets/added sodium (as well as potassium, chloride, magnesium). It is also important during the heat acclimation bout to familiarise yourself with your tolerance of pre-exercise fluid intake to ensure gastric comfort once exercise has commenced. There is a common misconception that you can gain more from heat acclimation by completing sessions dehydrated versus hydrated, however the literature shows this is unlikely to be the case. Hydrating well before and during heat acclimation is beneficial to your overall training and wellbeing through heat acclimation.

For specific advice by The International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN), they recommend pre-exercise hydration by ingesting ~500 mL of water or sports drinks the night before a competition, another 500 mL upon waking and then another 400–600 mL of cool water or sports drink 20– 30 min before the onset of exercise – although in the field/desert this may not obviously be viable.

Avoid Over Hydration

However, we advise you don’t “overconsume” water right before your heat acclimation training in attempt to increase hydration levels immediately (or each stage of the MdS legendary – although less likely due to rations), as it can lead to hyponatremia (low blood sodium levels) and can be dangerous to your health.

3. During the Heat Acclimation and the Marathon des Sables

Regular Intake

Aim to drink small amounts of water regularly rather than large quantities at once. This helps maintain steady hydration levels over a longer period of time. We recommend having a target amount that you want to drink each hour to help you stay hydrated – it’s also nice to have something to look forward to throughout the gruelling heat. On typical MdS courses, checkpoints are located every ~10 km for you to refill your water bottle(s) – but please check updated instructions, course and checkpoints. Therefore, by having a hydration strategy, you should utilize the water provided at these checkpoints wisely by planning your consumption and refills to avoid running out – in practice it may be that you consume water in the first ~5 km between checkpoints, as after this point water temperature may rise and instead be used to douse heads as it becomes somewhat undrinkable/unpalatable.

Electrolyte Balance

It’s advisable to use and trial your electrolyte/sodium tablets to replace sodium losses within your sweat. The advantage of this is that you can accurately measure the amount of sodium you’re taking in, and learn to tailor your intake to your personal needs. This is crucial in preventing cramping and maintaining muscle function, especially as there’s so much variability in sweat sodium losses between runners. Similar to the above, make sure you know how many sodium tablets you will need for each stage based off the target amount of water you want to drink each hour -and take more as a back up in case temperature peak above those expected. From our previous consultancy experience, participants have found it beneficial to have a mixture of flavours for electrolyte/sodium tablets to help with palatability across heat acclimation and the challenge itself.

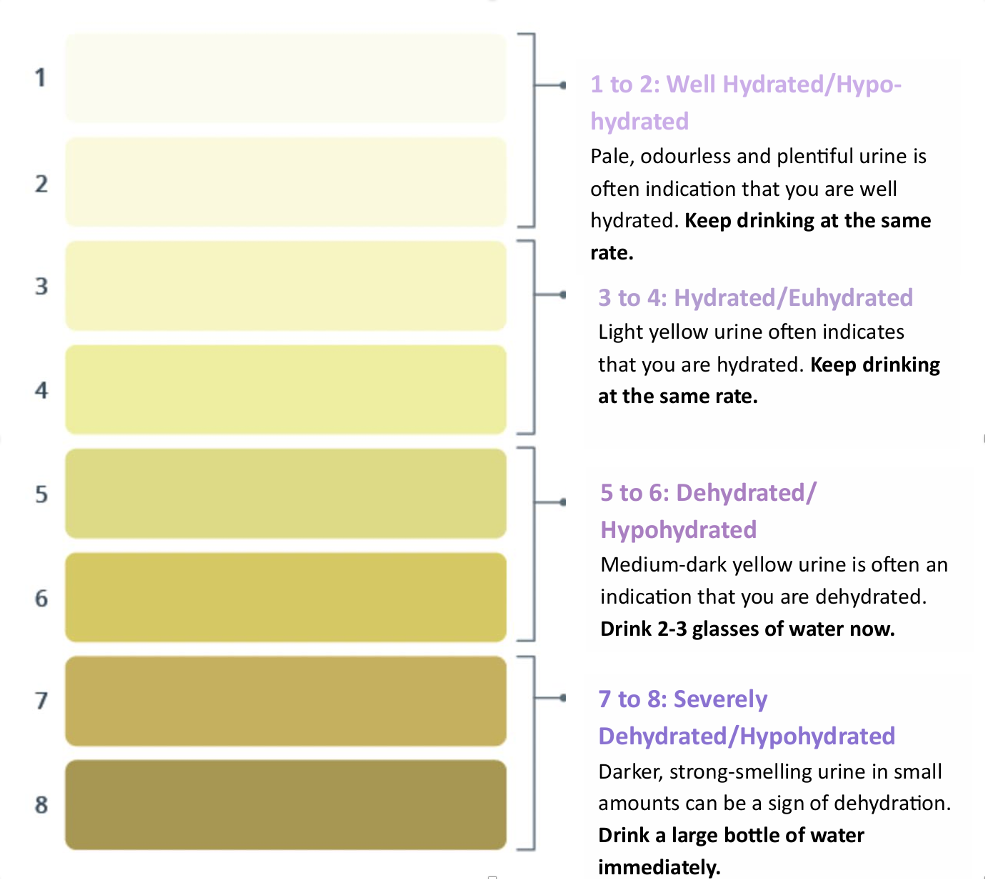

Check Urine Colour

In the field environment, you may wish to use the colour of your urine as a hydration indicator. Bear in mind that if this is your main indicator, then understand how supplements that may influence urine colour, for example vitamin C tablets, vitamin B2 supplements, orange flavoured multivitamin tablets and beetroot supplements (see the “How can I tell whether I am hydrated?” section below).

4. Post Heat Acclimation and Post Race Hydration

Rehydration

After each HA session, prioritise rehydration (and recovery). There is no need to replace large amounts of water immediately after each stage. Instead, focus on matching fluid intake to sweat loss, or up to 1.5 times sweat loss (or 150%) is recommended in the subsequent 1-2 hours following exercise. For races, you will receive a water ration when arriving to the bivouac. This is to be used for the evening and in the morning, and should factor in what is needed for cooking, cleaning, and drinking. It’s advisable to take electrolyte tablets to support effective rehydration too, for example Precision Hydration PH 1500 mg tablets (although other commercial ones exist). These can be used at the end of each HA session (sipped over 2-3 hours post-exercise) and MdS stage (ingested over the course of the evening). The additional sodium from this tablet likely helps your body to hold onto more of the fluid, meaning you pee less out and can maximise your blood volume and hydration status for the next session/stage and/or day. This ensures you are fully rehydrated and are not becoming depleted gradually over the course of the training or challenge.

Recovery Drinks

Use recovery drinks that contain a mix of carbohydrates and protein to help repair muscles and restore glycogen levels to ensure you are recovered for the next day. As mentioned in a previous article about heat stress and gut health, we know that exercising in hot conditions can highly modify carbohydrate (CHO) metabolism. Research suggests that CHO oxidation (carbohydrate use) increases during exercise in hot conditions compared with neutral temperatures. This is caused by a 25% increase in muscle glycogen use, and it results in increased blood lactate concentrations. However, heat stress reduces the blood flow to the intestine which may impair the absorption of carbohydrates (and other nutrients), which may lower the oxidation rate of ingested carbohydrates by up to 10%. So, although CHO use increases during exercise in the heat, there is a limitation in intestinal absorption and it’s not as simple as just ingesting more CHO. This highlights the need for heat acclimation (and also potentially gut training). A practical recommendation based on current evidence is to target 30-60 g of CHO intake per hour. Once again, practice this in training (HA sessions) as this may vary depending on your tolerance, HA status, and recent evidence suggests body size may impact absorption and use of carbohydrates. Finally, consider preference/taste and check out some of our recommendations for ultra-marathon training and race strategies here in The International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN).

5. Monitoring and Adjustment

Daily Check-ins

Get used to monitoring your hydration status daily (see the “How can I tell whether I am hydrated?” section below) and adjust your hydration strategy for the HA session or day if/where needed. For example, if you are dehydrated (also known as hypohydration) then you will need to increase the quantity of water and sodium that is consumed throughout the subsequent session / stage in comparison to the previous stage.

Know the Dehydration Symptoms

Educate yourself and pay attention to signs and symptoms of dehydration, for example you may feel and experience dizziness, high levels of fatigue, cramping, headaches, elevated heart rate and/or dark smelly and frothy urine.

6. Additional Considerations

Practice During Training

Test your hydration strategy during long training runs or heat acclimatisation/acclimation sessions (see sections below) to find out what works best for you and how effective the strategy is. This should include practising and getting comfortable with 1) drinking warm water as you will not have access to cold water whilst completing MdS, and 2) drinking water whilst running and/or slowing down and stopping to take on water.

Personal Supplies

Carry a hydration system (bladder and/or bottles) that is comfortable and easily accessible. Some runners prefer handheld bottles for easier monitoring of intake. However, avoid using the same bottles for your food/cooking and water source. Based on previous consultancy work, runners have found it beneficial to have one water bottle that is used for sodium and one water bottle that is used for plain water. Similarly, some athletes have found that separating their hydration and nutrition entirely is useful (i.e. by not using carbohydrate drinks, rather opting for separate nutrition and hydration products). Be mindful of the material of the bottles too, as plastic is likely to warm the fluids or even potentially melt/lose shape in the heat (you could wrap/insulate bottles to preserve temperature), and variety is key; multistage events are gruelling and therefore variations in the flavours of your sodium might be a welcome treat to help you get from check point to check point.

Body Weight Management

To help support your hydration strategy and avoid dehydration, it is important to educate yourself on what your normal body mass is through daily monitoring. For example, in the month leading up to the race you should be measuring and recording your body mass at the start of every day. This will allow you to see any changes and deviations in body mass of >2-5% (inferring dehydration). This is essential if you are also completing heat acclimation before MdS to assist with recovery between heat acclimation sessions.

Extra Weight Management

Be mindful of the extra weight of the water you carry. Balancing hydration needs with minimizing the weight you carry is crucial and must be considered and practiced in training. Based on previous consultancy experience, you can practice running with the weight of your pack during your heat acclimation sessions (see heat acclimation section below) to experience and get a greater understanding of what it will feel like to run with that weight, in those hotter conditions.

Heat Acclimatisation

This refers to repeatedly exposing yourself to similar conditions to the desert in a natural environment to help your body adapt to the heat. This means you would need to either fly out to the desert >1-2 weeks prior to the challenge or complete heat training in a similar location earlier in the year. However, not everyone has the financial capabilities nor time to do this and therefore heat acclimation is likely more favourable.

Heat Acclimation

This refers to repeatedly exposing yourself to artificially hot conditions similar to the desert via an environmental chamber for active strategies, or hot water immersion/sauna for passive strategies to help your body to adapt to the heat. The recommended duration is 10 x 1 hr sessions leading up to the challenge, especially if you have never completed heat acclimation before. More information on these training strategies can be found here.

Stay Informed

Keep up-to-date with any race-specific hydration guidelines provided by the Marathon des Sables organisers.

8. How can I tell whether I am hydrated?

There are two methods to assess your hydration status; 1) a simpler method including a urine colour chart (Figure 4), and 2) analysing a urine sample with specialist, yet reasonably cheap equipment (Table 1). Both methods determine whether you hydrated or not, and the severity of dehydration. The most cost-effective (~£25) and reliable method out of the two is analysing your urine sample using a refractometer. This is because the colour of your urine can be influenced by certain foods, medications and vitamin supplements, and maybe somewhat subjective.

This is something that you can measure at the start and end of each HA session or MdS stage to help inform your hydration strategy for the subsequent visit and/or stage of the race.

Figure 4. Urine Colour Chart.

Table 1. Urine Specific Gravity and Urine Osmolarity Interpretations.

| Urine Specific Gravity (arbitrary units) | Urine Osmolality (mOsm/kg) | Interpretation |

| 1.001-1.010 | <350 | Well hydrated/hyper-hydrated |

| 1.011-1.020 | 350-700 | Euhydrated/adequately hydrated |

| 1.021-1.030 | 700-1050 | Hypohydrated |

| >1.031 | >1050 | Severely hypohydrated |

Summary

In summary, the conditions you will face whilst undertaking the MdS Legendary have the potential to cause significant dehydration, which poses a major challenge to your performance and health whilst in the desert. Preparation is key to success, and this starts by understanding your own needs for water and sodium intake. Whether you use lab-based measures or cruder field-based methods, you can build, practice and refine your pre-planned hydration strategy during HA sessions before you arrive in Morocco. As a part of this, consider the practicalities of your hydration strategy, and what it looks like in reality in respect to the exact products and kit you will use to make your plan simple and easy to execute. Lastly, it’s important to remember that, just because it’s pre-planned, does not mean pre-set, and it’s vital that you are able to adjust on the go according to feedback on your hydration status within the race.

Further Reading, Contact Information, Resources & References

- Heat Acclimation at London South Bank University – https://shortcourses.lsbu.ac.uk/coursecart/viewitem/id,73

- Sweat Testing at Precision Hydration – https://www.precisionhydration.com/sweat-testing/our-sweat-tests/

- Gibson, O. R., James, C. A., Mee, J. A., Willmott, A. G., Turner, G., Hayes, M., & Maxwell, N. S. (2020). Heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance: a review and practitioner guidelines. Temperature,7(1), 3-36.

- Moss, J.N., Bayne, F.M., Castelli, F., Naughton, M.R., Reeve, T.C., Trangmar, S.J., Mackenzie, R.W. and Tyler, C.J., 2020. Short-term isothermic heat acclimation elicits beneficial adaptations but medium-term elicits a more complete adaptation. European journal of applied physiology, 120, pp.243-254. Stand, A.P., 2009. Exercise and fluid replacement. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 39(2), pp.377-390.

- Burke, L.M., 2001. Nutritional needs for exercise in the heat. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 128(4), pp.735-748.

- Racinais, S., Alonso, J.M., Coutts, A.J., Flouris, A.D., Girard, O., González‐Alonso, J., Hausswirth, C., Jay, O., Lee, J.K., Mitchell, N. and Nassis, G.P., 2015. Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 25, pp.6-19.

- Périard, J.D., Eijsvogels, T.M. and Daanen, H.A., 2021. Exercise under heat stress: thermoregulation, hydration, performance implications, and mitigation strategies. Physiological reviews.

- Stand, A.P., 2009. Exercise and fluid replacement. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 39(2), pp.377-390.

- Tiller NB, Roberts JD, Beasley L, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: nutritional considerations for single-stage ultra-marathon training and racing. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2019 Nov 7;16(1):50.

- Kerksick, C. M., Wilborn, C. D., Roberts, M. D., Smith-Ryan, A., Kleiner, S. M., Jäger, R., … & Kreider, R. B. (2018). ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. Journal of the international society of sports nutrition, 15, 1-57.