Challenges with running in the heat

Running in extreme heat stress is challenging and places a large physiological and psychological strain on the individual. Just as important is the awareness of heat-related injuries. These can range from mild including heat cramps and syncope (feeling light-headed or fainting), to severe including heat exhaustion (which may be commonplace for entrants in the Marathon des Sables), and up to the life-threatening heat stroke (especially if it is undetected or untreated). If you have trained well and adapted to the heat (via heat acclimatisation or acclimation), your body will cope better whilst running in the heat. You will therefore increase your chances of having a successful, enjoyable, and safe race experience.

If you have signed up for the Marathon des Sables (MDS) or other hot events of similar nature, it is vitally important that you:

- understand the conditions that you will compete in (Sahara temperatures can exceed ~45°C);

- recognise how well you respond to heat stress whilst exercising, and educate yourself on the possible warning signs/symptoms of heat-related illnesses;

- plan your preparation strategies leading up to departure date accordingly.

An article series on preparations for the MDS and exercising in the heat

This article is the first of three articles that focuses on pertinent questions posed by athletes and MDS entrants each year as they prepare for running in the heat.

This article series on preparation strategies for the Marathon des Sables include:

- Running in the Heat – Thermoregulation, Heat Stress and Heat Acclimation

- Heat Acclimation for Women

- Heat Stress & Gut Function: Nutritional Considerations for Running in the Heat

I caught up with Drs Ash Willmott, Jessica Mee, Justin Roberts and Neil Maxwell to get these common questions answered. They have supported numerous MDS runners in their preparation for the race, conducted a wealth of heat and performance related research and, Justin has even completed the MDS, and other ultra events, himself.

Whilst written with the MDS in mind, this article is useful and highly relevant for anyone training or competing in endurance and ultra-endurance events involving heat stress around the world. This includes regular marathons which can sometimes take place in very hot conditions.

Our response to exercising in heat stress

Mechanisms to prevent over heating

Firstly, lets talk some physiology and background theory. The body has four mechanisms to prevent over heating: conduction, convection, radiation, and evaporation of sweat. When the surrounding ambient temperature is hot, then the first three mechanisms result in only negligible heat loss, if any at all. This leaves us with evaporation of sweat as the only method by which the body can effectively regulate temperature under these conditions. This is also the mechanism that we can impact through heat acclimation.

Core temperature rising easily

It’s important to note that although morning temperatures in Sahara can be ~6-10°C in morning, these can rise rapidly to 25-30°C by mid-morning, continuing to rise to 35°C mid-afternoon and peaking around 40°C+, particularly in dune and exposed salt plain areas (it’s also not uncommon to have temperatures ~45°C on individual days, which results in even hotter temperatures in the sun. Therefore, it is worth stressing that core temperature could rise to 38-40°C fairly easily in sustained mid-day sun and possibly above 40°C (if not managing hydration and skin covering). When core temperature rises, we need to cool down and mitigate against hyperthermia or life-threatening internal temperatures (>40°C).

Evaporation of sweat

As such, the blood vessels dilate and the heart pumps warm blood out towards the skin’s surface (or peripheral circulation). There, some heat can be lost through conduction, convection or radiation if the conditions allow, whilst the majority will be lost through the conversion of sweat to vapour. Note that it is not the sweat itself that cools the body down, but the evaporation of it from the skin. This is a process which requires heat and is helped by air flow. The more we sweat, the greater the evaporation and the greater the cooling capacity, if the surrounding environment permits.

Negative responses when running in the heat

However, whilst running in the heat, the heart is hard at work pumping blood to the active skeletal muscles. At the same time, it is directing a proportion of blood flow to the skin’s surface for heat dissipation. In addition, fluid (and electrolytes) in the blood is being filtered and lost through sweat, thus leading to dehydration. Approximately 2-4% of body mass reduction can affect health and performance and easily achieved within 4 hours of daily running in the heat.

Consequently, the volume of blood returning to the heart with each beat decreases. This means that the heart has to work even harder (termed cardiovascular strain) to supply the body’s muscles and organs with oxygen and maintain blood pressure. All of which occurs whilst we’re also trying to protect our skin from prolonged UV exposure and sand irritation/blisters by wearing long sleeve tops, socks, and gaiters. Resultantly, this can lead to a range of negative responses, including:

- A higher heart rate,

- Increased energy expenditure,

- Dehydration,

- Increased core temperature,

- Feelings of discomfort or high exertion,

- Impairments to running performance,

- Dizziness, disorientation, and nausea,

- Heat-related illnesses.

It’s possible to adapt to heat stress

You may well have already experienced some of these, especially if you noticed a higher heart rate or slower finish time when exercising or competing in the summer months. The good news is that we can get more efficient at managing temperature regulation and adapt to heat stress. The key is getting this balance right between needing to get rid of the heat produced from the exercise and exacerbated by the outdoor conditions, but not wanting to lose too much fluid through sweat that leads to a cascade of negative effects. Likewise, understanding your own behavioural thermoregulation is an important way to look after yourself during the MDS race. You can achieve this through learnt experience and knowing how to pace appropriately for the hot conditions. That is when to slow down, when to take on fluid, and understand when emergency support may be required.

What’s the difference between heat acclimation and acclimatisation?

Most people signed up to the MDS don’t habitually live somewhere in 30-40°C heat, nor can they easily access these temperatures. Therefore, ensuring you’re sufficiently prepared with the induction of heat adaptations prior to the MDS start line should form part of your routine training, tapering and preparation strategy.

Heat acclimation is a method of training in heat stress within a controlled environment. This may be a climatic chamber, sauna facility or using over-dressing techniques. Heat acclimatisation on the other hand occurs in a naturally hot environment, such as the Canary Islands, Morocco, UAE etc.

Both methods can induce heat adaptations that take place within the body in response to repeatedly training in heat stress. For example, if you plan to travel to the desert two-weeks before the race, you would be “acclimatising”. If however you were to stay in the UK but undertake a heat chamber protocol for two weeks prior to flying to Morocco, you would be “acclimating”.

Choosing heat acclimation or heat acclimatisation?

There are key differences between the two methods, which may prevent or point you in the direction of one. These include:

- Cost, logistics and accessibility of travelling early

- Cost and location of equipment or facility hire

- Ease of accessibility to facilities

- Logistics and travel disrupting routine training/work commitments

- Disruption to quality of training

- Ability to control environmental conditions

- Professional expertise to support your heat training

- If you have had a prior, negative experience of the heat that you want checked out

What are the adaptations to heat stress that occur following heat training?

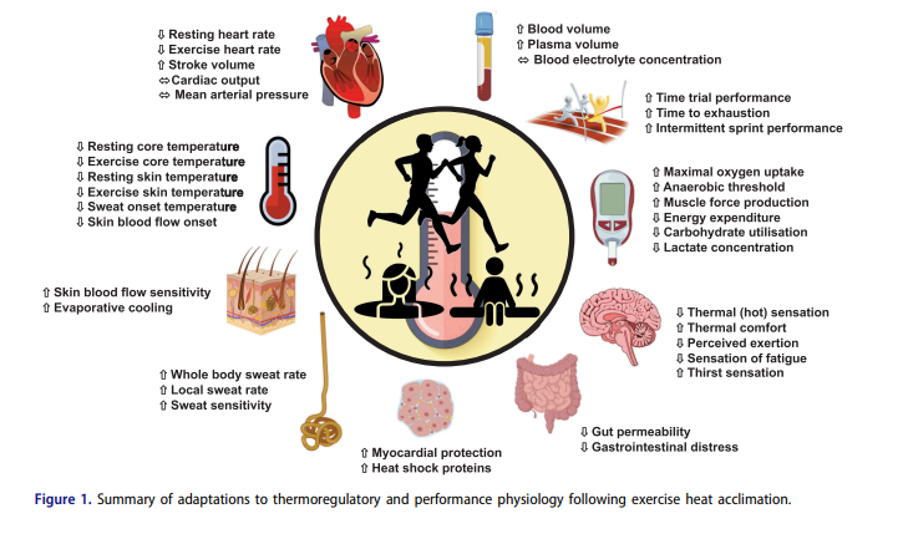

There are a large array of physiological and perceptual adaptations following successful heat acclimation and acclimatisation (as shown in the figure below from our recent review paper [Gibson et al., 2020]), in summary:

- Your resting and exercising core temperature reduces – meaning you can exercise for longer before reaching a high, unsafe core temperature.

- You become more effective in response to heat stress and sweat more. This means your sweat rate increases, more sweat can evaporate, and you can cool down better if conditions allow.

- You become more sensitive to heat stress and switch on your sweat response earlier. For example, you sweat earlier and more profusely at a lower core temperature.

- You lose less sodium in your sweat. The salt concentration in the fluids lost via sweating decreases, which is the body’s way of maintaining the salt balance.

- Your heart rate decreases and stroke volume increases. This is a result of your blood volume increasing (via plasma volume expansion) and, an improved blood pressure and cardiac output response towards the demands of exercising in heat stress.

- Your fitness levels (or maximal oxygen uptake – V̇O2max) and exercise performance in the heat increases.

- Your perceived rating of exertion decreases, and you begin to feel more comfortable whilst exercising or running in the heat.

- Finally, the number of and severity of heat-related illness symptoms lessen through heat acclimation.

As you can probably tell, these will all make a big difference when running in the heat of the desert.

If you’d like further information, you may wish to read Dr Ash Willmott and colleagues’ review article:

- Gibson, O. R., James, C. A., Mee, J. A., Willmott, A. G., Turner, G., Hayes, M., & Maxwell, N. S. (2020). Heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance: a review and practitioner guidelines. Temperature, 7(1), 3-36.

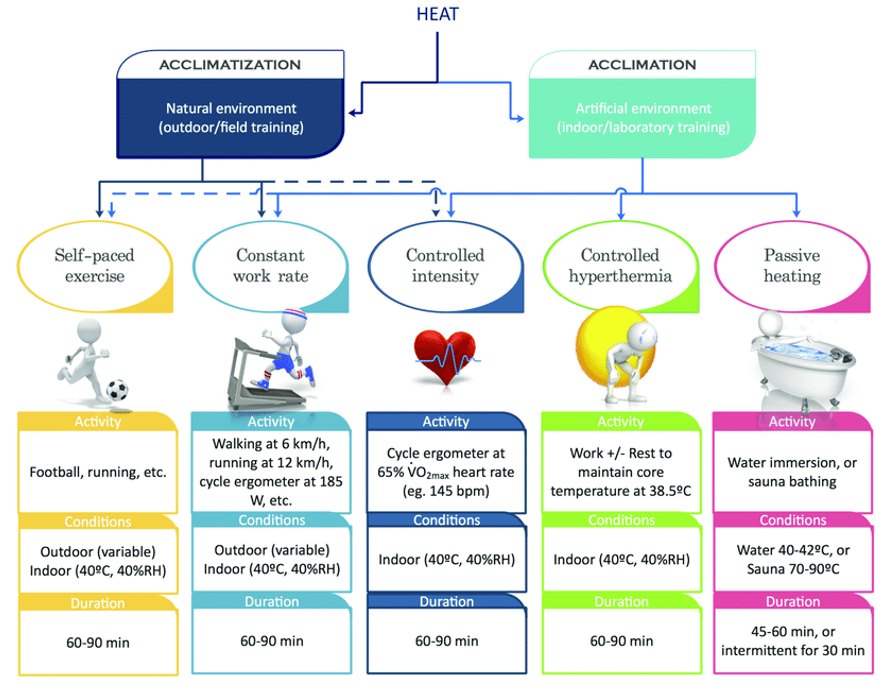

What are the evidence-based heat acclimation methods?

There are numerous methods used to adapt to heat stress. They include cycling sessions in a heat chamber, running in heat outside in hot natural conditions, or undertaking post-exercise sauna exposures and hot water bathing. All of these have their positives and negatives. However, the sections below will attempt to cover as many “hot topic” questions as possible and provide you with evidence-based practice. A summary of the typically used heat acclimation methods can be seen in the figure below (Racinais et al., 2019).

Is there an optimal heat acclimation method?

To optimise heat adaptations, we recommend that individuals undertake a controlled-hyperthermia heat acclimation strategy. This consists of exercising in a climatic chamber set to 40°C and 40% relative humidity. Typically via cycling as it’s non-weight bearing and can help lower exercise volume, which is especially important in a taper period. The individual targets an internal core temperature of 38.5°C, which is achieved within ~30-minutes when exercising at a designated pre-set intensity. You will then rest in the heat chamber, intermittently exercising to maintain core temperature at ~38.5°C for the remainder of the session (~60-minutes), totalling 90-minutes overall. This is then repeated over 10-14 consecutive days = medium-term heat acclimation (MTHA).

However, you can also undertake the traditional methods of constant work rate, which allow you to set a lower intensity for a prolonged period, which is much easier to administer and monitor. This means, for example, cycling at 50-60% of your maximal oxygen uptake or power output for 60-90 minutes.

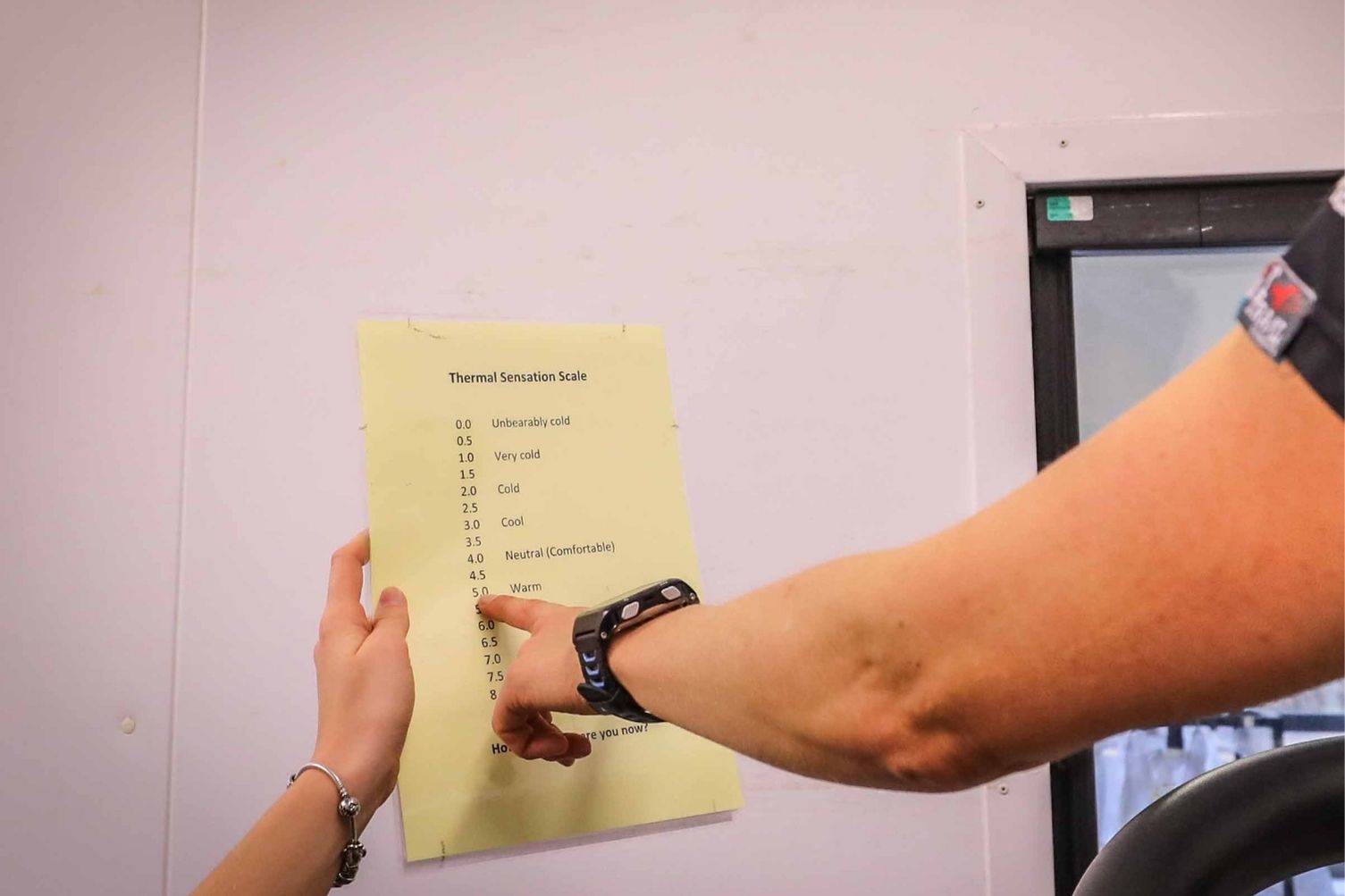

Maintain a core temperature of 38.5°C

Essentially, it is thought that the longer you remain hotter with a core temperature at or around 38.5°C, the greater the benefit. Why 38.5°C you ask? – well this is generally the core temperature that coincides with maintaining a good sweat response leading to adaptation. It also triggers other internal adaptations. Physiological (e.g. core temperature and heart rate) and perceptual (e.g. thermal discomfort and ratings of perceived exertion) variables would be routinely recorded and monitored to ensure safety is upheld at all times. Specific cut-off criteria should be in place should core temperature exceed 39.5°C or signs/symptoms of heat related illnesses occur. While these measures are there with safety in mind, they are also important in order to raise heat awareness and calibrate your internal barometer. Essentially this means that you become better at sensing how you are feeling. This is crucially important in the real environment.

When should this acclimation take place?

You can actually acclimate anywhere from 4-months prior to the Marathon des Sables (with the use of “top-up” heat training sessions thereafter), to 1-2 weeks directly before departure during the tapering stage. There is some evidence that we have what is called a molecular memory. Therefore, carrying out heat acclimation and then returning to it some months later will result in a quicker return to the heat acclimation state previously acquired. Key considerations that individuals face however, is the disruption to their training quality, cost and time availability, and the obvious decay in adaptations should you undertake heat acclimation too early and not maintain heat exposures.

Are there any shorter or alternative protocols that could work and are just as effective?

In practice it can be difficult to complete a series of heat chamber sessions for 10-14 days for people who are not full-time athletes. Considering work and life commitments, as well as time and cost constraints (as the above all requires specialist facilities and in the presence of trained professional staff), this is a common question.

The answer is that yes, there are plenty of other options. Some that work just as well, others that provide some benefit, but are less effective. However, “something is better than nothing” and as long as careful planning and health & safety is considered, there are various options. We lay out a sort of “pick & mix”approach below with alternative options.

I can access a heat chamber a few days before departure, is it worth it?

Yes, if you have the time, access, and funding for a few days in a heat chamber then we recommended you make the most of it. Even if just to experience the heat stress and familiarise yourself with how you feel when running in the heat it can be useful.

It’s unlikely that you’ll see significant adaptations in a couple of sessions. However, this may provide you with some confidence and awareness of the heat. You may learn how you respond (both positively and negatively) and how your kit works. You can practice with your running kit, drink temperature and equipment (e.g. shoes, gaiters and backpack). As mentioned, you may need to lower expectations of adaptations within this short period.

75% of adapatations can take place in the first 5 days

If you’re able to undertake approximately 5 days of heat training, termed “short-term heat acclimation” (STHA), we’ve seen positive adaptations occur in this time within MDS runners (Willmott et al., 2017). Research suggests that up to 75% of cardiovascular (e.g. heart rate reductions) and thermoregulatory (e.g. core temperature reductions) adaptations can take place initially. This is likely due to acute increases in plasma volume. You’re also likely to feel more comfortable and confident whilst exercising in the heat, just from familiarity. So, every exposure/training session counts!

I can’t access nor afford a few days in a heat chamber, is there anything else I can do?

Yes, there are still plenty of alternate options available when you can’t access specialised chamber facilities. Alternate methods which demonstrate promising, yet inferior adaptations compared to heat chamber methods, include repeated:

- sauna exposure,

- hot water bathing,

- hot yoga,

- exercise whilst overdressing and restricting heat loss.

Fortunately, sauna exposure and hot water bathing can be separate from training. You can undertake this post-exercise when you’ve already increased physiological strain, and this may help with efficiency and effectiveness. Further information can be found in the table below:

Example of evidence-based alternative methods for heat acclimation include:

| Hot water bathing: 10-20 minutes in 40°C separate from or following exercise, with time progressed up to 30-40 minutes over 5-10 days (Zurawlew et al., 2018). | |

| Sauna exposure: Post-exercise 30-minute sauna sessions in 87°C and 11% relative humidity for 10 consecutive days (Stanley et al., 2015) or ~100–108°C and 5–10% relative humidity, ~3 times per week for 3 weeks (Kirby et al., 2021) | |

| Hot yoga: 6 consecutive days of 60-minute hot yoga, consisting of 30 minutes of dynamic movements followed by 30 minutes of static stretching in 30°C and 48% relative humidity (Perrotta et al., 2018) | |

| Overdressing: 10 consecutive days of 50-minute cycling in 20°C and 37% relative humidity whilst wearing a sauna suit to restrict heat loss (Lundby et al., 2021) | |

| Warning: Caution and health & safety procedures are advised for all of the above methods.Start off at lower bathing/sauna temperatures and reduced times to gradually increase exposure duration. Additionally, there is a risk of dehydration, increased feelings of discomfort, fainting (via blood pressure changes) and, potentially drowning. Therefore, preparedness, common sense and professional advice is advised before beginning these alternate methods. | |

Effectiveness of alternative heat acclimation methods

Typically, we observe larger magnitudes in heat adaptations following exercise in heat stress, as opposed to passive bathing/sauna exposure. This is due to the increased and prolonged physiological strain. Nonetheless, these alternate options offer cost effectiveness, easier accessibility, and less disruption to routine training. We advise, as outlined below, to not use overdressing for anything other than increasing strain for heat acclimation means. That is don’t use it for acute weight loss and make sure you begin any heat training well hydrated.

How much heat acclimation is necessary for adequate adaptation?

We categorise heat acclimation as short-term (STHA) = ≤ 5 days, medium-term (MTHA) 6–10 days and long-term (LTHA) = >10 days. Typically, the longer the protocol = the more enhanced and optimal adaptations occur. Historically both MTHA and LTHA present “maximal” adaptation versus STHA.

Shorter strategies can be desirable for an athlete. However, whilst 75% of heart rate and/or core temperature reductions may occur within approximately 5 days, this is not universal. Therefore relying on this may result in sub-optimal or no adaptations at all if planned poorly.

How long should heat acclimation sessions be?

The typical duration of each exercise heat acclimation session is 60-120 minutes, irrespective of the specific method used. Passive sauna or hot bathing duration lasts from 10-40 minutes. Usually session length is progressed as individuals adapt and cope better with these methods.

Overall, the duration of the session is likely determined by availability and cost of the chosen method. Whilst longer durations are more beneficial, we advise careful consideration and monitoring of health & safety.

Do I have to complete heat acclimation sessions across consecutive days?

No, there is growing evidence that heat acclimation sessions can be completed intermittently. This allows for sufficient rest and recovery between specific heat acclimation, for example every 2-3 days (Willmott et al., 2018). You could also do two sessions on the same day and then rest from them for a couple of days. Whilst traditionally heat acclimation sessions would be completed over consecutive days, this can be a limiting factor. For many it can cause disruption to their training and/or work schedules. Therefore, not having to do this can be helpful during a taper period as well as periods of high volume training.

When should heat acclimation take place?

It can be challenging to schedule heat acclimation prior to the Marathon des Sables when many runners want to get into the heat chambers at the same time. Therefore, it can be wise to not leave heat acclimation to the last minute. Sufficient and well-planned heat acclimation could occur well in advance of the MDS, up to 4-8 weeks prior to departure. Even if you are visiting a facility that houses a purpose-built environmental chamber that can control temperature and humidity in the week to 10 days before you fly out, get in touch much sooner. Practitioners should carry out a needs analysis where they collect information about your training level, health and history, prior experience in extreme ultras, any prior injuries – both musculoskeletal and heat, and of course your availability.

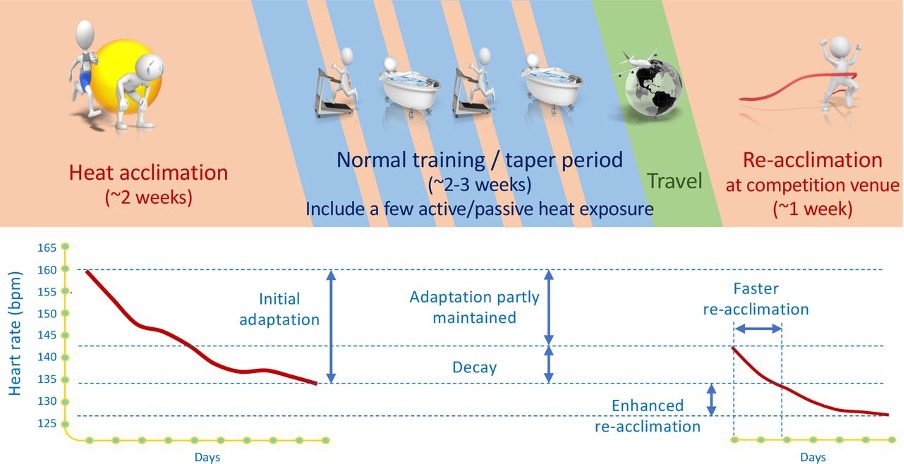

Option: acclimate in advance and top up nearer the event

Following a “block” of heat acclimation, you could “top up” your heat training with intermittent single or repeated heat acclimation sessions in the lead-up to competition, thus, this way your important tapering strategy will not be disrupted (as per the image below [Racinais and Periard, 2020]).

For example, a 5-10 day “block” of heat acclimation could occur in a heat chamber in January. You could then follow this up with “top up” sessions using sauna exposure, hot bathing or exercising whilst overdressed intermittently prior to your departure for the MDS.

Adaptations can last 2-3 weeks

Following 5-10 days of heat acclimation, adaptations typically last for 2-3 weeks thereafter if you don’t include any further heat exposure (i.e. no top-ups). It has however been suggested that “for every day of heat acclimation undertaken, the adaptation will be retained for two days”. Therefore, you don’t want to acclimate too early, nor leave it too late, thus, planning is essential. Remember, you could always travel to the race earlier and re-acclimatise naturally too.

Don’t overdo it in your taper period

If you plan to undertake heat acclimation in the final two to three weeks before the race, be mindful of your overall stress load. Whilst manageable, it will coincide with your taper, as well as last minute pre-race panic, stress and maybe some sleepless nights. Therefore, don’t put undue pressure on yourself during these weeks. If you have a daily or near daily heat acclimation session in the form of heat chamber, sauna, hot yoga, or running with a sweat suit, don’t add more training on top. You need to arrive at the start line fresh and rested. Every day in the final couple of weeks should gradually take you there – don’t overdo it!

What might happen if I ignore heat acclimation?

We advise that all athletes prepare for exercise in heat stress ahead of your arrival to the start line. The best is of course to try and induce adaptations. However, even a one-off familiarity to heat stress during active or passive exposures to “get a feel for the heat” is still better than nothing. This is due to the increased physiological strain on the body when running in the heat. This strain can lead to mild to severe heat-related illnesses, impair your performance, incur feelings of discomfort and spoil the experience.

You may wish to read stories from the Environmental Extremes Laboratory (EEL) led by Dr Maxwell, who have supported runners for the MDS in: 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2021.

Elisabet’s note: also consider reading about the very hot edition of MDS 2021 here, where more thorough attention to heat acclimation could likely have helped many competitors.

Is a one-off pre-screening test beneficial?

The benefit of education about you respond in the heat

Yes, we place high importance on the education runners receive whilst exercising in the heat chamber. This includes learning about their own physiology, heart rate zones, sweat rates, predicted race pace, and thermal comfort; all of which can inform runners on how hot they are when they feel hot. This helps them to recognise cues as to when to stop and take on fluids, slow their pace and lessen the risk of experiencing heat related illnesses (for example behaviour thermoregulation).

What is a heat tolerance test (HTT)?

As there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach, part of your preparation strategy may include a one-off heat screening or heat tolerance test (HTT) assessment. Especially if you have suffered from prior heat illness (e.g. heat exhaustion or heat stroke) and/or gastrointestinal issues when you undertake long-duration exercise or exercise in hot conditions. This test simulates the expected ambient temperatures of Sahara (~40-45°C) and likely exercise intensity or race pace, within a controlled laboratory environment. It offers a range of useful outcomes:

Benefits of a heat tolerance test

- Familiarisation to exercising in hot conditions where you can experience how you respond physiologically and perceptually against a fixed exercise intensity where normative data of other athletes exists. This allows you to see how you fair along a continuum of heat tolerance. For example, Mee et all (2015) from the University of Brighton developed a running heat tolerance test (30-min at 9 km.h-1 and 2% gradient, in 40°C and 40% relative humidity) that was found to be reliable and sensitive to heat adaptation following heat acclimation.

- Identify factors which may contribute to heat-related illnesses. For example a very high exercise core temperature, a low sweat rate or high sweat sodium concentration.

- Typically, when we administer HTT in an environmental chamber, we would carry this out without the need for fuel or fluid to compare progress between pre and post heat acclimation.

- You could carry out home-based heat tolerance tests yourself. In these you exercise over a fixed route, before and after a block of home-based heat acclimation. If you keep the same speed and monitor heart rate and how hard it feels, this will give you a gauge of how you have adapted. Weighing yourself before and after to determine whether your sweat rate has improved will also indicate adaptation.

- Familiarisation to fuelling and hydration strategies whilst exercising in heat stress could be useful. This would allow athletes to assess their gastrointestinal tolerance to fluid and their nutritional strategies.

- Heat tolerance tests and heat acclimation sessions can enable you to test your equipment in the heat. This may highlight any friction or irritation issues.

- Completing a heat tolerance test before and after a block of heat acclimation enables practitioners to evidence the physiological and perceptual adaptations under controlled environments. For the athletes it is all part of the combined physiological and education value that collectively brings heat awareness prior to the MDS.

Summary: Guiding Principles for Heat Acclimation

We advise:

- Undertake heat acclimation to experience exercising in heat stress and to induce adaptations.

- Tailor heat acclimation methods to your own needs and requirements. Perhaps utilise a range of exercise, passive and/or post-exercise heat stress via heat chamber, hot water bathing, or sauna exposures.

- Heat acclimation session should be ~60-90 minutes in duration. Repeat these over 5-10 consecutive or intermittent days, with use of “top up” sessions as required. Seek professional advice when planning heat acclimation, especially if you have any underlying health conditions. Consider health & safety at all times.

- Solicit the help of a friend when you plan to expose yourself to heat stress, for observation. Monitor physiological variables regularly (especially during your first few sessions where you shouldn’t go unsupervised).

- Assess hydration status pre-heat stress, where you should begin hydrated and rehydrate with 150% of lost fluid effectively.

- Apply a familiarisation to heat stress, where you progress exposure time and/or ambient temperature gradually. Start off with a shorter time and lessened heat stress initially to prevent any acute heat related illnesses.

- Plan your heat acclimation well in advance and schedule into your training and/or tapering phase – don’t leave preparation to the last minute.

Further Reading, Contact Information, Resources & References

Here is a related article on heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance:

- Gibson, O. R., James, C. A., Mee, J. A., Willmott, A. G., Turner, G., Hayes, M., & Maxwell, N. S. (2020). Heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance: a review and practitioner guidelines. Temperature, 7(1), 3-36.

Twitter:

Dr Ash Willmott – @AshWillmott / https://aru.ac.uk/people/ash-willmott

Dr Justin Roberts – @drjustinroberts / https://aru.ac.uk/people/justin-roberts

Dr Neil Maxwell – @UoB_EEL / https://research.brighton.ac.uk/en/persons/neil-maxwell

Read more about the Environmental Extremes Laboratory (EEL) = https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/extremeslab/2021/12/13/eel-team-mitigate-effects-of-severe-heat-stress-in-35th-marathon-des-sables-reflections-from-the-athletes-and-team/

If you are interested in:

- Heat acclimation, screening or research aligned to this area – contact Dr Ash Willmott or Dr Neil Maxwell

- Nutrition guidance for endurance and ultra-endurance events – contact Dr Justin Roberts

- Altitude exposure, information and education – contact Dr Ash Willmott or visit Para-monte.org

References:

- Gibson, O. R., James, C. A., Mee, J. A., Willmott, A. G., Turner, G., Hayes, M., & Maxwell, N. S. (2020). Heat alleviation strategies for athletic performance: a review and practitioner guidelines. Temperature, 7(1), 3-36.

- Kirby, N. V., Lucas, S. J., Armstrong, O. J., Weaver, S. R., & Lucas, R. A. (2021). Intermittent post-exercise sauna bathing improves markers of exercise capacity in hot and temperate conditions in trained middle-distance runners. European journal of applied physiology, 121(2), 621-635.

- Lundby, C., Svendsen, I. S., Urianstad, T., Hansen, J., & Rønnestad, B. R. (2021). Training wearing thermal clothing and training in hot ambient conditions are equally effective methods of heat acclimation. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport.

- Mee, J. A., Doust, J., & Maxwell, N. S. (2015). Repeatability of a running heat tolerance test. Journal of Thermal Biology, 49, 91-97.

- Perrotta, A. S., White, M. D., Koehle, M. S., Taunton, J. E., & Warburton, D. E. (2018). Efficacy of hot yoga as a heat stress technique for enhancing plasma volume and cardiovascular performance in elite female field hockey players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(10), 2878-2887.

- Racinais, S., Casa, D., Brocherie, F., & Ihsan, M. (2019). Translating science into practice: the perspective of the Doha 2019 IAAF world Championships in the heat. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 1, 39.

- Racinais, S., & Périard, J. D. (2020). Benefits of heat re-acclimation in the lead-up to the Tokyo Olympics. British journal of sports medicine, 54(16), 945-946.

- Stanley, J., Halliday, A., D’Auria, S., Buchheit, M., & Leicht, A. S. (2015). Effect of sauna-based heat acclimation on plasma volume and heart rate variability. European journal of applied physiology, 115(4), 785-794.

- Willmott, A. G., Hayes, M., Waldock, K. A., Relf, R. L., Watkins, E. R., James, C. A., … & Maxwell, N. S. (2017). Short-term heat acclimation prior to a multi-day desert ultra-marathon improves physiological and psychological responses without compromising immune status. Journal of sports sciences, 35(22), 2249-2256.

- Willmott, A. G., Hayes, M., James, C. A., Dekerle, J., Gibson, O. R., & Maxwell, N. S. (2018). Once‐and twice‐daily heat acclimation confer similar heat adaptations, inflammatory responses and exercise tolerance improvements. Physiological reports, 6(24), e13936.

- Zurawlew, M. J., Mee, J. A., & Walsh, N. P. (2018). Heat acclimation by postexercise hot-water immersion: reduction of thermal strain during morning and afternoon exercise-heat stress after morning hot-water immersion. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 13(10), 1281-1286.